Why are Housing Costs so High?

A Look at the Forces Driving Up Housing Costs and Solutions to Address It

The housing production crisis has fully gripped the state, marked by a severe lack of price-attainable homes and apartments and a drastic increase in homelessness.

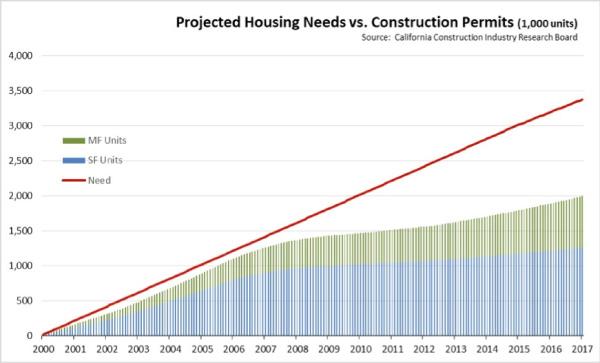

For far too long, we have not built enough homes to meet our state’s housing demand. As you can see in the graphic below, the housing supply deficit in our region has grown at an astounding rate in the last ten years with no signs of slowing down. Unless we dramatically begin to build new housing at the levels necessary to both make up for past deficits and keep up with population growth, housing prices and homelessness rates will continue to rise, exacerbating current problems.

THE MISSING MIDDLE – Locally, the worst housing supply crisis is for workforce housing. Despite a Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) projected need of 13,728 moderate-income units; the City of Los Angeles has only permitted 275 units since 2013 ( 1 ). The situation in the County was even more severe with not one single moderate-income unit permitted ( 2 ). Public subsidies are insufficient for lower-income households; however, they are nearly non-existent for middle-income households. At the same time, development is too difficult and too costly for workforce housing projects to be feasible. Therefore, middle-income households don’t qualify for below-market rate housing units and are left to scavenge for more and more expensive market-rate housing, along with most low-income households that can’t find subsidized housing. By producing more naturally-occurring workforce housing, the market would naturally lessen the burden on both lower and moderate-income families.

Like Southern California, Seattle’s unprecedented population growth and a soaring economy has driven housing prices skyward within the past decade. However, a steady supply of new housing units in some of Seattle’s most desirable communities has helped prices to finally stabilize ( 3 ). Rents have dipped 2.9% in the last quarter, amounting to between $50-100 per month savings for the average renter ( 4 ). The supply of housing is finally outpacing the number of new renters, giving the market some much-needed relief ( 5 ).

Taking cues from Seattle, we must begin to remove the supply restraints in our region and increase inventory to bring about true housing affordability. This paper discusses the following root causes of the housing production crisis and puts forth several key solutions that can be implemented at the state, regional, and local levels.

This action plan takes a closer look at some of the forces behind our region’s exorbitant housing prices, followed by practical and effective solutions that can help increase housing supply at every income level, thereby driving down costs.

Appendix A

Large California City Urban Infill Affordable Housing Project on City Land

Units: 102, including 1 BR, 2 BR, and 3 BR units

Income Requirements: Extremely-Low to Low-Income

Developer-Proposed Amenities: community room, public meeting space, public art, teenager activities, rooftop deck, environmentally sustainable.

Result: not built

In addition to the above developer-proposed amenities, the City requested parking in excess of the zoning, and robust services for all residents, including car sharing service, child care, retail office space set aside for a nonprofit office, and ground lease for City land. Additionally, the City proposed minimal local jurisdiction investment, and asked for 85% of developer cash flow generated from income after debt.

The magnitude of special requests increased construction costs, which, combined with the lack of income potential and city subsidy to pay for these special requests, rendered the project financially infeasible and the project was abandoned. A developer who takes a gamble on this project will not have a financially sustainable model for services, maintenance, and upkeep, which could result in the development quickly becoming a slum.

Affordable housing developers already face mountainous challenges, including increased construction costs, increased interest rates, a decrease in subsidized financing, decrease in tax credit pricing, a lack of available land, and community opposition. As this example demonstrates, piling on additional costly and unnecessary requests can kill even a well-designed and well-planned project that would be valuable to the community.

Footnotes

1 Los Angeles Department of City Planning (2016). Annual Element Progress Report. Retrieved from: https://planning.lacity.org/policyinitiatives/Housing/APRs/2016_APR.pdf, page 9.

2 Los Angeles County Department of Regional Planning (2017, March 21). General Plan and Housing Element Progress Reports for 2016. Retrieved from: http://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/supdocs/112305.pdf, page 40.

3 Mudede, Charles. “Seattle-Area Rents Drop to a Level Still Far From Affordable for Most, “ January 25, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.thestranger.com/slog/2018/01/15/25713850/seattle-area-rents-drop-to-a-level-thats-still-far-from-affordable-for-most

4 Rosenberg, Mike. “Seattle-area rents drop significantly for first time this decade as new apartments sit empty,” January 12, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.seattletimes.com/business/real-estate/seattle-area-rents-drop-significantly-for-first-time-this-decade-as-new-apartments-sit-empty/

5 Id.

6 Southern California Association of Nonprofit Housing (2017). Los Angeles County Renters in Crisis: A Call to Action, pg. 1.

7 Fermanian Business & Economic Institute at Point Loma Nazarene University. (2015). Opening San Diego’s Door to Lower Housing Costs, pg. 9.

8 California Home Building Foundation. (2017). Impacts of a Prevailing Wage Requirement for Market Rate Housing in California, pg. 3.

9 California Center for Jobs & Economy. (2017). Regulation & Housing: Effects on Housing Supply, Costs and Poverty, pg. 3.

10 Id.

11 Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, City of Portland (2018). “One Year Review of Inclusionary Housing Zoning Code and Program.” Retrieved from: https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/article/672661

12 Id.

13 Armbrister, Molly. (2017, September 12). Affordable housing fee collections will fall far short of projections. Retrieved from: https://www.bizjournals.com/denver/news/2017/09/12/affordable-housing-fund-collections-will-fall-far.html

14 Id.